KV5 is not open to the public, although it may be the most interesting of the tombs inthe Valley of the Kings.

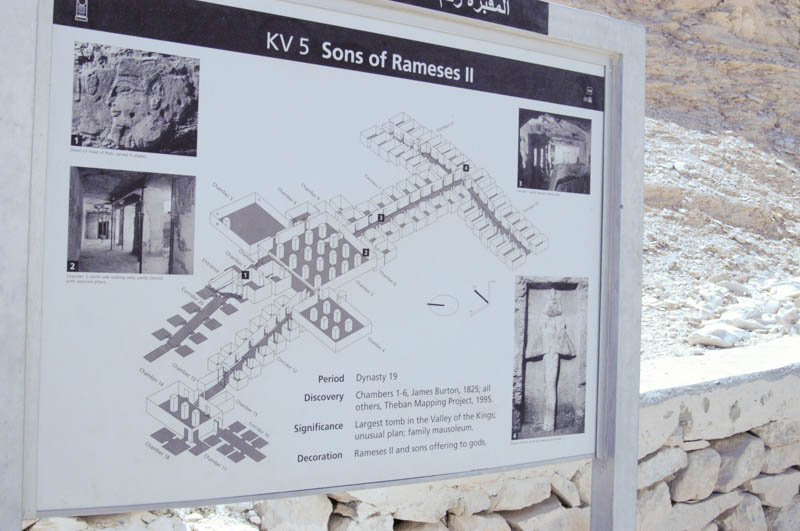

KV5 is the tomb of the sons of Ramses II and may be the largest tomb in the web Bank, but it lay undiscovered for centuries, filled with rubble and sand that has washed through the valley. A number of egyptologists investigated the tomb in the last century, but they never got past the first chambers and abandoned the tomb as “uninteresting”.

However, in the late 1980’s the Theban Mapping Project revisited the tomb and decided to clear it (mostly to make sure that building projects nearby to enhance the Valley of the Kings for tourists would not be damaged). For the first few years, they were also quite convinced that the tomb was “unremarkable”. However, in 1995 the group discovered long corridors lined with rooms — over 120 so far — most likely containing the burials of some of the sons of Ramesses II. Most tombs in the valley contain only six to eight chambers.

The tomb may have originally been from Dynasty 18 and expanded by Ramesses II. At least six sons of Ramesses are known to be buried here, although the Theban Mapping Project believes that since more than 20 representations of sons decorate the walls of the first eight chambers, that at least that many sons were buried here. Unfortunately, many of the names were destroyed by flooding and rubble — even though egyptologists know the names of 52 of his sons (Ramesses was reputed to have 186 or so!).

The sons currently identified in the tomb are Mery-atum, Mane-kher-khepsehf (oldest son), Ramessu, and Sethy. Two sons not associated with this tomb are Khaemwese and Merenptah, as they have their own tombs.

The first phase of the tomb was done before Ramesses usurped it for his sons. The second phase was finished during his lifetime. Phase three continued work after his death until the Christian period in phase IV when it was robbed extensively.

Decorated in raised reliefs cut into a lime plaster applied to prepared rock surfaces. Some plaster remains, but marks remain where the artists cut through the plaster to the rock. Every wall – at least so far – was decorated.